E37: Resilience engineering with Lorin Hochstein

Download MP3An interview with Lorin Hochstein, resilience engineer and author. Our discussion was about how to handle a complex system that falls down hard and – especially – how to then prepare for the next incident. The discussion is anchored by David D. Woods' 2018 paper, “The Theory of Graceful Extensibility: Basic Rules that Govern Adaptive Systems”, which (in keeping with the theme of the podcast) focuses on a general topic, drawing more from emergency medicine than from software.

Lorin Hochstein

Lorin Hochstein

Mentioned

- Brendan Green, "The Utilization, Saturation, and Errors (USE) method", 2012?

- How Knight Capital lost $500 million very quickly. Link and link.

- Lucy Tu for Scientific American, "Why Maternal Mortality Rates Are Getting Worse across the U.S.", 2023

- David Turner, A Passion for Tango: A thoughtful, Provocative and Useful Guide to that Universal Body Language, Argentine Tango, 2004

- Fixation over fomites as the transmission mechanism for COVID: Why Did It Take So Long to Accept the Facts About Covid?, Zeynep Tufekci (may be paywalled)

- The safety podcast about a shipping company flying a spare empty airplane: PAPod 227 – What-A-Burger, Fedex, and Capacity, Todd Conklin, podcast

Correction

On pushing, pulling, and balance, A Passion for Tango says on pp. 34-5: "The leader begins the couple's movement by transmitting to his follower his intention to move with his upper body; he begins to shift his axis. The follower, sensing the intention, first moves her free leg and keeps the presence of her upper body still with the leader. [...] The good leader gives a clear, unambiguous and thoughtfully-timed indication of what he wants the follower to do. The good follower listens to the music and chooses the time to move. The leader, having given the suggestion, waits for the follower to initiate her movement and then follows her." He further says (p. 34), "As a leader acting as a follower, you really learn quickly how nasty it feels if your leader pulls you about, pushes you in the back or fails to indicate clearly enough what he wants."

Apologies. I was long ago entranced by the idea that walking is a sequence of "controlled falls". Which is true, but doesn't capture how walking is a sequence of artfully and smoothly controlled falls. Tango is that, raised to a higher power.

On pushing, pulling, and balance, A Passion for Tango says on pp. 34-5: "The leader begins the couple's movement by transmitting to his follower his intention to move with his upper body; he begins to shift his axis. The follower, sensing the intention, first moves her free leg and keeps the presence of her upper body still with the leader. [...] The good leader gives a clear, unambiguous and thoughtfully-timed indication of what he wants the follower to do. The good follower listens to the music and chooses the time to move. The leader, having given the suggestion, waits for the follower to initiate her movement and then follows her." He further says (p. 34), "As a leader acting as a follower, you really learn quickly how nasty it feels if your leader pulls you about, pushes you in the back or fails to indicate clearly enough what he wants."

Apologies. I was long ago entranced by the idea that walking is a sequence of "controlled falls". Which is true, but doesn't capture how walking is a sequence of artfully and smoothly controlled falls. Tango is that, raised to a higher power.

Credits

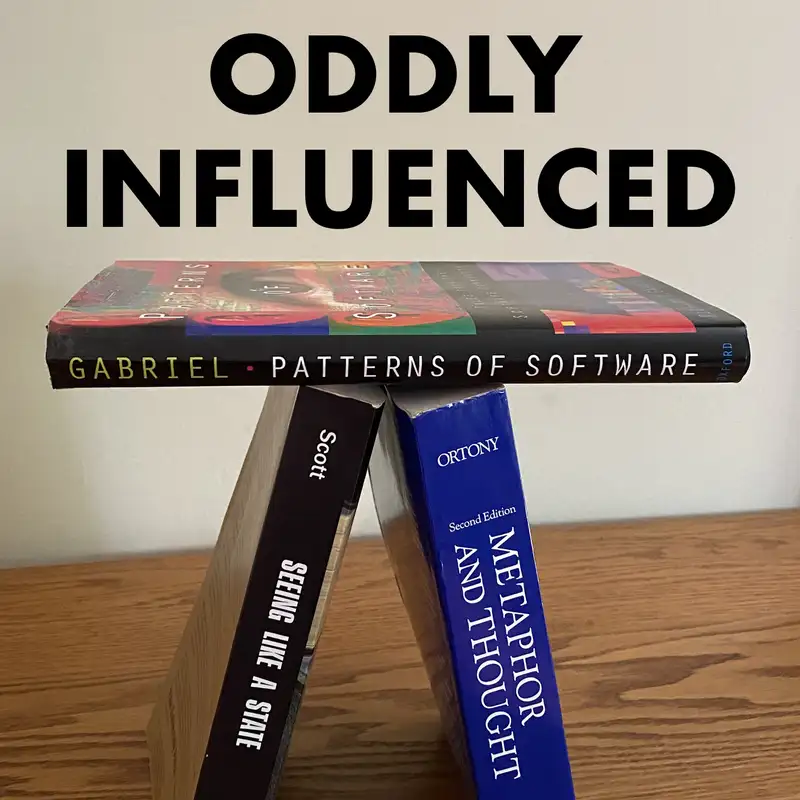

The episode image is from the cover of A Passion for Tango. The text describes the cover image as an example of a follower's "rapt concentration" that, in the episode, I called "the tango look".

The episode image is from the cover of A Passion for Tango. The text describes the cover image as an example of a follower's "rapt concentration" that, in the episode, I called "the tango look".