E30: Foucault, /Discipline and Punish/, and voluntary panopticism, part 1

Download MP3Welcome to oddly influenced, a podcast about how people have applied ideas from *outside* software *to* software. Episode 30: Foucault and voluntary panopticism, part 1

The so-called “Snowbird workshop” happened 20-some years ago. It brought together representatives of several styles of software development that, at the time, were far from the mainstream. If I remember right, there were two explicit topics for the workshop.

First, these styles all seemed to have *something* in common. The workshop asked: what was it? The result was the Manifesto for Agile Software Development (both the four values and the twelve principles).

Second, these styles were usually called “lightweight methods”. That term lacked marketing pizzazz, so a better one was needed. The term arrived at was “Agile”.

While Agile certainly was a better name, I concluded within two years that it had two big disadvantages:

First, everyone assumes they know what “Agile” means. That is, they have a picture in their head of how “agility” applies to bodily movement through space, and reason by analogy to software development. Well, marketing terms don’t work that way, any more than you can properly deduce what spraying “Glade Air Freshener” does to a room from your mental image of a grassy open space in a forest.

The second problem was that everyone assumed they already *were* Agile. After all, what’s the alternative? They’re torpid? They’re clumsy?

So I became a tongue-in-cheek proponent of alternate terms that avoided those problems, most notably “artisanal retro-futurism crossed with team-scale anarcho-syndicalism”. Never has anyone said, “I understand exactly what that means, and it describes what I already do.”

Another tag I’ve used is “voluntary panopticism”. These two episodes are about why that term’s appropriate – at least to the original style of Agile. My main sources are Michel Foucault’s 1975 book, /Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison/ and C.G. Prado’s 2000 second edition of /Starting with Foucault/.

≤ music ≥

Foucault was an interesting character. People who complain about postmodernism or “cultural marxism” or relativism or what the French did to the social sciences and humanities, are complaining about Foucault, maybe more than about anyone else.

Broadly speaking, his topic was power – defined idiosyncratically – and how power affects what people know, how people behave, and how they think of themselves. /Discipline and Punish/ is one of his key books, though I’ve read that he later backed off from some of its conclusions.

Foucault’s approach was roughly historical, but he was not a historian, so historians tend to think he oversimplifies scandalously and that he concentrates too much on how historical people *talked* about what they were doing – or what they were *going* to do – rather than what they actually did. For example, he draws conclusions from plans of prisons that were never actually built or that, when built, were used differently than intended.

However, he’s full of ideas and so fits this podcast’s mandate: to ask, not “is this idea true?”, but rather “how would we act if it were?” I’ll go a bit further and say that the behavior of early Agile teams adds some evidence that Foucault was onto something.

≤ short music ≥

There’s a spectrum of opinions about people of the past. One extreme is that they were basically just like us. That’s typically associated with the “nature” side of the “nature vs. nurture” debate. Such people are prone to saying things like, “We evolved as hunter-gatherers on the savannah, that imprinted our psychology, and so people today can be explained with respect to that ‘environment of evolutionary adaptedness’”. We are – at all times, everywhere – status-driven, utility-maximizing creatures whose relationships between genders are fairly fixed because mothers cannot evade a heavy commitment (at least nine months) to their young, whereas fathers can impregnate and scurry away. Or, more generally, people have physical bodies in a physical world, and the brute facts of physical reality have more power to shape us than do social forces or our culture.

The other extreme (the one Foucault is at, mostly) thinks social forces – nurture – dominate nature. The human mind can be fairly analogized to a “blank slate” that is written on by society. Different people in different societies can think arbitrarily differently.

Now, to me, it seems obvious that the truth is somewhere in the middle, and that the relative power of nature or nurture is going to depend on the issue at hand. But that’s boring, and I want to say that *emotionally*, I favor the “socially constructed” side of the argument just because it’s more interesting. It’s the same reason I like science fiction that depicts aliens as *alien*, not just humans with a personality trait like aggression or cowardice dialed up to 11. (Looking at you here, Larry Niven.)

Heck, I find parts of my own society interestingly bewildering. I cannot envision what it would be *like* to be emotionally connected to a sports team to the point that their loss in a national or global tournament would gut me, cast me into despair. Yet, I only have to point to, say, the entire nation of Argentina to show that people think differently in important ways. So why should I expect that I could *really* understand – from the inside – how people from 18th century Europe and America reacted to – or thought about – crime?

Because that’s the topic of /Discipline and Punish/. Foucault argues that, roughly during the latter part of the 18th century, Europe (with France as his focus) shifted from one “epistēmē” to another. An epistēmē (or episteme, if you’re American, which I am) is essentially a conceptual framework that determines how we think the world works: what people are *for*, what questions are worth asking, what counts as evidence, how causes relate to effects, and so on. It’s pretty closely related to what Kuhn called “paradigms” in his /The Structure of Scientific Revolutions/. Kuhn claims it’s somewhere between hard and impossible for a scientist in one paradigm (phlogiston-based chemistry, for example) to understand what people from a different paradigm are even *talking about*. The same is true of epistemes. It’s hard for us, who live in the post-1800 episteme, to understand what people from 1650 meant when they used words like “crime” or “punishment”.

Fortunately, Foucault is here to translate for us.

≤ music ≥

Robert-François Damiens tried to kill the French king Louis the Fifteenth in 1757. /Discipline and Punish/ starts out with a bang by describing his execution, which was very elaborate, sadistically painful, and ended with him being pulled to pieces by six horses (after the traditional four couldn’t do the job).

Foucault then switches to eighty years later and Léon Faucher’s rules for young prisoners in Paris. For example:

“At the first drum-roll, the prisoners must rise and dress in silence, as the supervisor opens the cell doors. At the second drum-roll, they must be dressed and make their beds. At the third, they must line up and proceed to the chapel for morning prayer. There is a five-minute interval between each drum roll.”

That punishment is more recognizable to us today, though with what seems like a weird obsession with micromanaging the prisoners’ time. How did punishment by confinement come to replace punishment that was almost exclusively based on doing physical damage to people’s bodies?

Foucault starts by asking why old-style punishments were so severe – what purpose did they serve?

The obvious answer would be deterrence. And it sure seems like that ought to have worked. If I was, say, a random Parisian, I might see someone paraded through the streets with a sign on him saying he was a thief. I would be encouraged to fling mud at him. Along with the rest of the jeering crowd, I’d follow him to where the gallows were set up and watch him be hanged. I like to think that would have motivated me to never ever steal a cow, which was the specific crime behind this example.

However, it doesn’t seem to have worked. There was a whole lot of crime, especially violent crime. Here’s a quote from the paper “Crimes and Punishments in Eighteenth Century France”:

“Given that repressive measures had so little apparent effect on the frequency of crimes of various types, criminality as a variable seems to have been rather independent of judicial action.”

In fact, violent crime was decreasing in the first part of the 1700s while punishments for violent crime were getting more extreme. That’s not to say that there wasn’t still crime, but the composition of crime shifted over the century. More on that in a bit.

(A side note here: the decline of violent crime didn’t change people’s firm opinions that it had been increasing the whole time. In my lifetime, I’ve certainly seen *that* dynamic a time or two.)

So, if you asked people in the 1700s why hanging was an appropriate sentence for cow theft, they might *say* deterrence, but it sure seems like something else was going on.

That something else was vengeance. I’d summarize Foucault’s argument like this:

France was an absolute monarchy. The king was supposed to have effectively infinite power. Any lawbreaking was a direct attack on the King, a defiance of his power, a damage to his person. It’s something like an invasion of his kingdom, except at least an invasion is by a peer ruler, not some *subject*.

The reaction had to be a counterattack in which the sovereign demonstrated not just power, but an overwhelming excess of power. “Shock and awe”. The purpose was not to right a wrong, or even to punish, exactly, but to show everyone that the King’s power is still unbounded despite that one insect’s behavior.

“The public execution, then, […] is a ceremonial by which a momentarily injured sovereignty is reconstituted. It restores that sovereignty by manifesting it at its most spectacular. The public execution […] belongs to a whole series of great rituals in which power is eclipsed and restored (coronation, entry of the king into a conquered city, the submission of rebellious subjects). Over and above the crime that has placed the sovereign in contempt, it deploys before all eyes an invincible force. Its aim is not so much to re-establish a balance as to bring into play […] the dissymmetry between the subject who has dared to violate the law and the all-powerful sovereign who displays his strengths.”

The object of the proceedings wasn’t the condemned man or even the crime. It wasn’t even the watchers, not exactly, at least not as people to be influenced. The real audience was the universe, or God.

≤ music ≥

OK, so within 80 years, imprisonment goes from being an uncommon punishment to the overwhelmingly dominant kind of punishment. Why did inflicting pain *upon* the body shift to regimenting the body, with an obsession about making it do certain things at certain times in a certain place – namely, the prison?

It happened in two steps. Foucault is very much not a fan of the idea that effects have simple causes, but – just between you and me – I’m going to say the first step was because of The Enlightenment. In particular, a new theory of society that caught on, that of the “social contract”. According to a new cohort of social theorists, society was an agreement among its members to obey society’s rules. And the lawbreaker hadn’t.

“The citizen is presumed to have accepted once and for all, with the laws of society, the very law by which he may be punished. […] The least crime attacks the whole of society, and the whole of society – including the criminal – is present in the least punishment. […] The right to punish has been shifted from the vengeance of the sovereign to the defense of society.”

And defending society isn’t limited to deterring the criminal from reoffending. He is, if anything, the lesser concern. The more urgent problem is the example he sets.

“The injury that a crime inflicts upon the social body is the disorder that it introduces into it: the scandal that it gives rise to, the example that it gives, the incitement to repeat it if it is not punished, the possibility of becoming widespread that it bears.”

The deterrence here is aimed at preventing *non-criminals* from *becoming* criminals, although I think Foucault would say that people of this time didn’t really think in these terms, that judicial reformers of the day didn’t habitually consider people to have such fixed natures.

Instead, this being the Age of Reason and all, they aimed to make it easier for everyone to react to their temptation to commit a crime by reasoning that would be a stupid thing to do.

It would work like this:

First, a lot more criminals should be caught. In the previous episteme, the great damage done by the punishment was combined with a small and haphazard chance of being caught. (I won’t go into it, as it’s not super relevant, but I’ll note that my understanding of modern criminology agrees: the likelihood of punishment matters way more for deterrence than the amount of punishment. So score one for French intellectuals of the late 1700s.)

Next, people would be constantly reminded that crime is punished. They should see – and keep seeing – criminals repaying what was now conceived of as their “debt to society”. Think clearly-labeled prisoners doing public works projects. Better than killing a killer, wrote a 1781 reformer, would be turning him into someone “forced to spend the rest of his days repairing the loss that he has caused society.” Some conceived of the ideal punishment as making the crime-doer a slave that any citizen could boss around for the period of punishment. (If you’ve read the book /Too Like the Lightening/, you’ll remember that this is exactly the situation of its narrator. I would be astonished – given the other worldbuilding and the author’s background – if these real-world proposals weren’t her source for that plot point.) And if the prisoners weren’t visible enough, “men as well as boys should be taken to the mines and to the work camps and contemplate the frightful fate of these outlaws”.

In addition to the continual visibility of punishment via work – and somewhat contradictory to it – the mental link between crime and punishment was thought to be strengthened if the punishment was “made to conform as closely as possible to the nature of the offense, so […] those who abuse public liberty will be deprived of their own; those who abuse the benefits of law and the privileges of public office will be deprived of their civil rights; speculation and usury will be punished by fines; theft will be punished by confiscation; ‘vainglory’ by humiliation; murder by death.”

Note that imprisonment is not a main means of punishment. Prisons had a bad reputation as basically places where a sovereign stashed away inconvenient political rivals, not a tool for the use of society. Reformers of this era disliked prisons because:

1. The punishment isn’t mentally associated with the crime (except for a few crimes like kidnapping).

2. It has no effect on the public’s thinking, because the actual punishment – and the actual punished person – is hidden away.

3. Instead of “paying their debt”, prisoners sit around doing nothing, which is bound to multiply their vices. And society is paying for all this!

Basically, prisons didn’t have a connection with reason, with literally changing the mind of the criminal and also the rest of society. So they were not a proper solution to the problem of crime.

Our reformers were also minimaxers. Crime gained the criminal some benefit. Crime could be deterred by making the punishment *just enough* of a cost to the criminal that a sensible person wouldn’t choose crime. As Beccaria put it in 1764, “For punishment to produce the effect that must be expected of it, it is enough that the harm that it causes exceed the good that the criminal has derived from the crime.”

≤ pause ≥

I have to admit I find this view of crime and punishment rather appealing, but the approach only lasted about 20 years. Figures.

≤ music ≥

Why did the whole western world change from a movement that was against prisons to our modern world, where prisons are by far the main means of punishment, except I guess for white-collar criminals?

Foucault assumes that there’s no such thing as “a spirit of the age” or an easily-identifiable cause of social change. He’s more along the lines of software consultant Jerry Weinberg’s motto that “things are the way they are because they got that way”. JavaScript isn’t the way it is because of the historical inevitability of prototype-based object systems. It’s the way it is because, partly, one fan of prototype systems needed to produce something fast, and also because of lots of different actors found it useful to go with this one (let’s face it) crude prototype.

Although Foucault staked out an intellectual position against the idea of historical inevitability, and in favor of complex and semi-random causation, I’m happy to produce a more conventional, “this caused that” story. To make it more memorable.

My story begins with the Prussian Army of Frederick the Great. Starting in 1740, he turned it into an army very good at winning wars. Frederick himself credited specific battlefield success to rate of fire and maneuverability. That latter included marching in cadence, something that went out of favor after the Romans. Marching in cadence allows people to clump together more tightly, which allows you to make maneuvers like turning 90 degrees much faster, which is amazingly useful for Frederick’s favorite tactic, the “oblique order of battle”.

You achieve rate of fire and maneuverability with training, training, training, to the point where the necessary movements become automatic reflexes. Moreover, the most effective training, allowing fast and flawless performance, came from breaking a task down into individual steps.

Because of Prussian successes, other armies began to copy their training approach. Here’s a French example from 1766. It covers the steps involved in getting your rifle ready to fire. Sorry about the length.

“Bring the weapon forward in three stages. Raise the rifle with the right hand, bringing it close to the body so as to hold it perpendicular with the right knee, the end of the barrel at eye level, grasping it by striking it with the right hand, the arm held close to the body at waist height. At the second stage, bring the rifle in front of you with the left hand, the barrel in the middle between the two eyes, vertical, the right hand grasping it at the small of the butt, the arm outstretched, the trigger-guard resting on the first finger, the left hand at the height of the notch, the thumb lying along the barrel against the moulding. At the third stage, let go of the rifle with the left hand, which falls along the thigh, raising the rifle with the right hand, the lock outwards and opposite the chest, the right arm half flexed, the elbow close to the body, the thumb lying against the lock, resting against the first screw, the hammer resting on the first finger, the barrel perpendicular.”

If you can visualize that – I can’t – you’ve got what it takes to be in the Prussian Army.

What strikes me about that is it seems an awful lot like a computer program. You’ve got a series of steps. You’ve got `while` loops of the form “while not perpendicular to the right knee, do: move rifle.” So I dub this period “The First Great Age of Programming”, ours being the second.

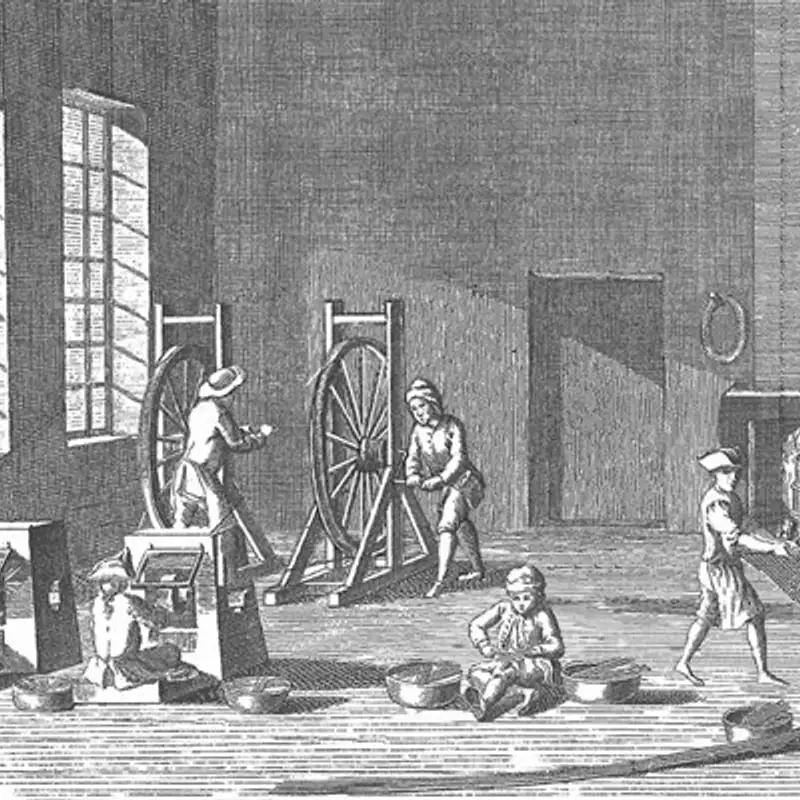

This is also the age of the factory. We associate the industrial revolution from 1760 to 1830 as being mainly a British thing, but lots of people were taking work that used to be done in scattered workshops and centralizing it in “manufactories”. Moreover these early factories leaned heavily into division of labor.

Adam Smith’s 1776 /The Wealth of Nations/ has a famous description of division of labor in a pin factory:

‘One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on, is a peculiar business, to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper; and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations, which, in some manufactories, are all performed by distinct hands.'

The key innovation of the division of labor is that each individual “processing unit” doesn’t have to be good at any large task, but instead maximally efficient at one small task. As a zillion people have pointed out, that encourages the boss to ignore the humanity of the worker. Whereas the owner of a craft workshop gets stuck dealing with the messy individuality and variability of his employees, the factory foreman need only concern himself with training the worker in one task, monitoring performance, and – if necessary – swapping out an inadequate worker for an identical, but more performant, one.

Monitoring performance turns out to be really important because the *scale* of things was changing a lot in this period. A man intent on conquest had to project his will onto a much larger army than was previously the case. A factory owner had to do the same for many more people than did a workshop owner. The same was true for owners of the rapidly growing agricultural estates.

So, as the actions of workers simplified, the job of overseeing them got more complicated. That led to an emphasis on *observability*.

Foucault writes of a factory, built in 1791, whose entire bottom floor was devoted to block printing fabric. There were 132 tables, divided into two rows, each table with two people, one to spread color on a carved block of wood, the other to press the block against the fabric. The floor was organized for observability:

“By walking up and down the central aisle […], it was possible to carry out a supervision that was both general and individual: to observe the worker’s presence and application, and the quality of his work; to compare the workers with one another, to classify them according to skill and speed.”

The result of these trends was a society crazy about efficiency and programmability. The attitude behind military training and factory work spread everywhere. For example, good handwriting is obviously important (thank goodness I wasn’t alive then), so it’s important to program students, who must:

“hold their bodies erect somewhat turned and free on the left side, slightly inclined, so that with the elbow placed on the table, the chin can be rested upon the hand […]; the left leg must be somewhat more forward under the table than the right. A distance of two fingers must be left between the body and the table; for not only does one write with more alertness…” etc. etc. etc.

And it’s important to instill automatic reflexes in the children in the same way that soldiers were trained to respond instantly to commands:

“When prayer has been said, the teacher will strike the signal at once and, turning to the child whom he wishes to read, he will make the sign to begin. To make a sign to stop a pupil who is reading, he will strike the signal once… To make a sign to a pupil to repeat when he has read badly or mispronounced a letter, a syllable, or a word, he will strike the signal twice in rapid succession […]” etc. etc. etc.

These people were *weird*, but Foucault says we live in the world they made.

≤ short music ≥

Continuing on, let’s look at criminality. Prior to this period, criminality was mainly about violence: doing injury to people’s bodies. During this period, the crimes actually committed shift to property crimes. Part of that is because there’s a lot more property around. In the show notes, I link to a graph that shows the change in gross domestic product in Britain over time. It’s stunning how much riches the industrial revolution created.

But the relentless focus on efficiency also had an effect on what we might call “folk theories of society”. The abortive Age of Reason approach viewed people, at their best, as citizens who thought. That was supplanted by a view of people as, in their essence, machine-like *workers* who *produce*.

The criminal is no longer a person who thinks badly. He’s now a person *with a bad attitude*. Specifically, he’s *lazy*. He steals because he doesn’t want to work. It’s his *character* – his *reflexes* and habits – that need to be fixed, not his thinking.

In the next episode, I’ll discuss how the thought leaders of the factory age designed that fix. Since they’d applied drill, observation, and rigid discipline to produce the better soldier, student, and factory worker, they naturally did the same when it came to reforming the criminal.

However, the details are interesting, especially since Foucault claims they basically created a feedback loop that ran out of control to create the world we live in today. And, moreover, to create *the kind of people* we are today. That’s true even though the approach didn’t actually *work* as well in the prison as it did in the factory or the army, but we all know about doubling down when you don’t get the results you want.

Here’s a teaser. If I can make it work, the next episode will also include a short discussion of the cult horror movie “Cube” that I swear could have had Foucault as an uncredited contributor. If you like that sort of movie, give it a watch before next time.

Thank you for listening. I’m really grateful that people listen to the oddball connections I make.