This is not an episode (a diversion into what makes explanations good)

Download MP3Welcome to oddly influenced, a podcast abou–≤record scratch≥

The title of this episode is “This is not an episode”. That’s because I’m obsessed about having this podcast provide ideas for improving software practice. This episode isn’t going to do that.

Instead, I’m going to talk about explanations. I think I’m pretty good at explaining things, and enough people agree that I made a living at it for 30-some years. The long-story-short version is that explanation is all about the use of examples, counterexamples, and stories.

The 1998 book /Communities of Practice/ makes a good case study because – I claim – it doesn’t explain the theory of communities of practice very well. Why not? Because the book’s *theory* gives reasons why examples, counterexamples, and stories are so important. But the book has way too few of them!

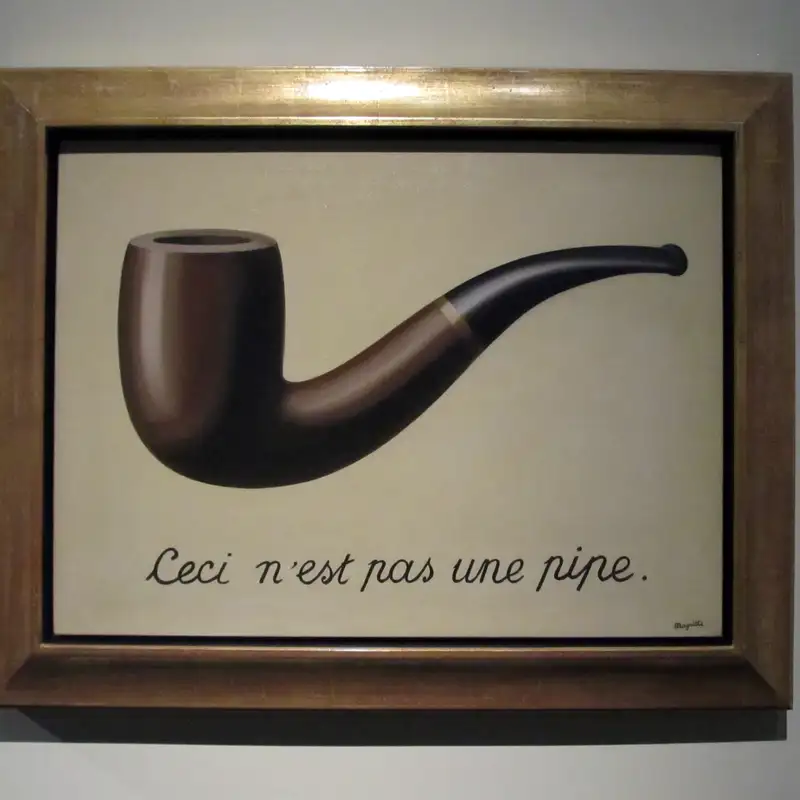

The way the book supports its own argument by not putting its own argument to use scratches my old Lisp programmer itch for self reference. It’s something like that thrill of understanding (even if only momentarily) the Y combinator or the writing of the French post-structuralist Jacques Derrida. Except way easier to explain than either of those.

So this episode is about building explanations, not about building software.

It’s only very tangentially useful to those interested in understanding “communities of practice”. One reason is that I don’t understand the book’s explanation very well, so my explanation will be shallow, ignore a good chunk of the theory, and could well be flat-out wrong in important places.

That’s probably OK because what people in the software business mean *today* when they say “communities of practice” (and they seem to say it a lot, more than I thought) is *not* what the 1998 book is about. So if you’re in a conversation about, say, a corporate initiative to set up communities of practice, nothing in this episode will be of any practical value.

You will not hurt my feelings if you don’t listen to this episode, though that doesn’t mean you should send me a note rubbing it in.

≤ music ≥

Still here? Let me lay out some history.

Episode 20 was largely about how people transmit knowledge and history and group identity through storytelling. It was based on Julian Orr’s research in the mid-1980’s.

Jean Lave and Étienne Wenger built on Orr’s work and related anthropology work to produce a theory of learning through “legitimate peripheral participation”. Their 1991 book – and my episode 21 – explained that theory. It noted that such learning happens in “communities of practice”, but it didn’t explain the term: “The concept of ‘community of practice’ is left largely as an intuitive notion, which serves a purpose here but which requires a more rigorous treatment.”

Wenger gave that more rigorous treatment in his 1998 book /Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity/, which was to be the original topic of this episode. Except that after about 10 part-time days of highlighting and rereading and putting notes in Tinderbox and making outlines in Bike, I realized I simply did not understand communities of practice well enough to be sure I would be explaining them well enough.

That could be because I don’t have the right background to make sense of the book, but I noticed something when looking at the secondary literature: people who *did* have the right background seemed also to be confused. It seemed sort of the opposite of the blind men and the elephant: everyone was *saying* “communities of practice” while pointing at different things in the world.

A tipping point in the story of the term was the publication of Wenger, McDermott, and Snyder’s 2002 book, /Cultivating Communities of Practice/, which was pitched at corporate executives and was written in the style of airport bookstore management books. I’ve no problem with that – you tailor things differently for different audiences – but it seems to me that the theory and practice had changed. Even the book’s subtitle – “a guide to managing knowledge” – hints at that. It makes “management” central, whereas management is much more peripheral in the 1998 book. Now, granted, I’m allergic to management books, so I read only as far as a Kindle sample would let me (some distance into chapter 2), but that was enough for me to agree with Andrew Cox in his 2005 paper “What are communities of practice? A comparative review of four seminal works”: “Now, the definition [of community of practice] is of a group that are somehow interested in the same thing, not closely tied together in accomplishing a common enterprise. The purpose is specifically to learn and share knowledge, not to get the job done. This is genuinely a different concept from that proposed in Wenger (1998), not just a change of tone or position; it is simply a different idea.”

(Note that Wenger, as of his 2010 paper, “Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems: the Career of a Concept”, seems to disagree that he’s moved on to what is “simply a different idea”. Still, it seems to me he *has*, in the same sense that modern Scrum is simply a different idea than the Scrum of 2001: both in terms of having changed over time, and in the sense of that change filing off the rough edges in a way that makes it more congenial to the management status quo. To be uncharitable, the 2002 version of “communities of practice” – the one that you’ll encounter in your organization – seems to me a somewhat souped-up form of meetups or special interest groups. Nothing wrong with those, I should say – I quite enjoy them myself – but that’s not the kind of learning I was wanting to explain when I started this three-part series of episodes.)

So, that’s the history. I offer it to make this claim: if the history of the theory shows that much disagreement, the 1998 book didn’t explain it well. In my own writing, I try to make my default assumption that if a reader doesn’t understand something, it’s my fault. And if a lot of people misunderstand me, it’s *definitely* my fault.

≤ short music ≥

The book’s purpose is to help the reader learn something, so its own theory of learning ought to apply. That theory is rather radical.

To Wenger, you know something if you have experience using it. You know what a square is not because you’ve memorized a definition, but because the idea “square” is a kind of summation of all your experience with squares. If you listened to episode 21, you can see again the emphasis on learning through doing.

That is, learning definitions is not essentially different than learning to ride a bike or how to do surgery or how to find bugs in computer programs.

Moreover, learning is *fundamentally* social. Knowledge arises with what Wenger calls “the negotiation of meaning”, a key term that I do not understand. But it happens through the interaction of you with someone else (maybe an imaginary someone else, if you’re reading a book, or if your brain, like mine, contains an unstoppable narrative that isn’t directed at me, exactly, but some usually-unspecified “other”).

So. If essentially no learning is what my dad used to dismissively call “book learning”, and you want people to learn about communities of practice, and they have to do it through a book, how do you write that book?

You have to give them a history of simulated experiences, and you somehow have to simulate social interaction.

You simulate experiences with examples. Not just tossed-off example words as in “The repertoire of a community of practice includes routines, words, tools, ways of doing things, stories, gestures, symbols, genres, actions or concepts that the community has produced [etc. etc.].” Those single words don’t carry enough of a sense of experience. *How* is a “gesture” included in a repertoire?

To be fair, Wenger does use 18 pages to describe medical insurance claims processors, and he does draw some longer examples from there, but not nearly enough in my opinion, and not in enough detail to give *this* reader anything like an experience of having one of the book’s concepts as part of my repertoire, or how such a repertoire item differs from a “reification”, which is also a key concept in the book.

That highlights a grievous lack, which is the *counterexample*. I am willing to bet that a good part of any practice of “negotiation of meaning” are questions like “So, X is a reification?” and responses like “Well, maybe, but I’d call it more a part of the repertoire because ≤ fill in explanation here ≥.”

Examples give experiences of what’s *inside* the inevitably fuzzy boundary of a concept, and counterexamples give experiences of what’s *outside*. Learning, to Wenger, really has to be an ongoing process of “renegotiating” those boundaries. New examples or counterexamples might draw a boundary more clearly. Or new experiences might cause a community – or a reader – to relabel an old example as now being outside the boundary, changing the concept.

A book that contains examples and counterexamples can simulate the back-and-forth of social interactions and thus stimulate learning. I do that deliberately when writing books. Starting with the fantastically underselling /RubyCocoa: Bringing some Ruby Love to OSX Programming/ but continuing in more successful books, I’ve had a habit of pushing beyond my knowledge of a topic, misunderstanding something, *putting that misunderstanding in the book*, *leaving it there*, but having later text correct it. I like to think that simulation of my learning experience both helps the reader with more examples and also makes me as author more of a character, more of the reader’s conversational partner: thus making reading more of a social experience. (Note to authors, though: it’s all fantastically inefficient because it requires a lot of rewriting to get a story that flows.)

With that in mind, I will now talk about my teeth.

≤ music ≥

In my excessively nerdish teen years, I was *horrible* at tooth-brushing, and I have the fillings to show for it. But in the 50ish years since then, I don’t mind saying that I am widely recognized as a pretty damn good tooth brusher. I don’t get cavities any more. So how did my tooth-brushing practice go from lousy to exemplary?

Here’s an example. Once I was having my regular dental visit. As usual, the dental hygienist cleaned my teeth – scraping away plaque and poking at places that might be new cavities or old fillings starting to fail. She told me there was a particular group of teeth that I didn’t brush well enough, allowing plaque to build up. That was the lower front teeth, on the inside, the side the tongue is on. (Which Dawn tells me is the “lingual” side, from the Latin word for tongue.)

Ever since then, I’ve paid special attention to the lingual side of my front teeth. And dental hygienists no longer tut tut me about plaque.

What parts of Wenger’s theory – and what parts of his terminology – does this story illustrate?

First, I’ve had many, many experiences of brushing my teeth. Those experiences form a pattern in my mind that I can use to evaluate any experience and say, “that’s tooth-brushing”, or “that’s not tooth-brushing”, or “that’s kind of tooth-brushing, but kind of not” (for example if I was lost in the wilderness and cleaned my teeth with my forefinger). Such a pattern is something like knowledge, except that Wenger thinks knowledge is social and tied to a social understanding of *competence*.

I only *know* how to brush teeth if I meet community standards of tooth brushing. What community, you ask? Well, the community of people who devote attention to the practice of brushing teeth and have formed opinions about doing it well.

In my story, my hygienist and I are a part of such a community. In that visit, we found out we had different ideas about competent tooth-brushing, specifically about how much effort to spend on that lingual side. Were I the sort of person who was an internet expert on epidemiology in 2020, international relations and warfare in 2021, and inflation and macroeconomics in 2022, I might have argued with her. I mean, I might have attempted to “negotiate meaning” with her.

Since I’m not, I didn’t. I changed my knowledge of tooth brushing to include increased attention to that part of my mouth.

Another aspect of that learning was that there was a new thing in my world. I’m guessing a dentist would call it the lingual side of the incisors, but to me it’s just “that area back there”. Importantly, that new thing in my world is something I orient or organize my tooth-brushing practice around. Wenger says that’s a recurring feature of learning: a community creates a new “reification” – an idea that’s treated like a thing and becomes a focus of part of group practice.

A non-tooth example would be the Github pull request. It’s a reification of certain core assumptions, such as that the code base is fragile and that changes to it are not to be trusted without scrutiny. Notice that’s an importation of open source assumptions – where indeed you might get a pull request from someone you’ve never heard of – an importation into supposedly jelled teams. That is, a reification affects not only practice but also attitudes, and by doing so, Wenger would argue, people’s self-identification of what it *means* to be a programmer on a team. In a way, that particular reification contributes to cascading adjustments to other ideas about the nature of software, team work, and so on, and those downstream adjustments ripple through practice. A pull request is never just a simple, value-free, text-like object in a database.

One possible value of Wenger’s work is to remind us to question what exactly it is that we’re reifying and what side-effects that reification is having.

Before continuing, I want to try to cement the social and historical aspects of learning. The lingual side of teeth is a new term for me, and I bet I’ll remember it better than most terms I learn. Why? Because I learned it while having a particular experience – going on a walk with Dawn, telling her of my struggles understanding Wenger’s book, saying how I’d gotten the idea that tooth-brushing might somehow be used as an example. The word “lingual” has that specific history associated with it. Another part of the word’s history is my experience of using it in this episode’s script, and my tying it to the earlier concept of “reification”.

Remember the war stories from episode 20? I’m certain they were full of details. Those details make experiences memorable and thus promote learning. That’s why advanced math books are so notoriously forbidding: the definition-theorem-proof definition-theorem-proof style is a poor match for human learning. That’s why I remember more from my undergraduate degree in English literature than from the math courses I took during my other, simultaneous, undergraduate degree, the one in math and computer science.

Anyway. I’m not here to fix mathematics pedagogy. I’m here to tell you about tooth brushing.

I also learned to pay special attention to the parts of the tooth nearest the gum, that I should use a soft rather than a medium toothbrush, and that I should brush with an up-and-down “wiping” motion instead of a side-to-side scrubbing motion.

I won’t give you the details, partly because – really – how much do you want to hear about my teeth, but also because I hope you’ll find my bare recitation of brushing facts doesn’t really “stick” in your brain, compared to the lingual story, reinforcing my point about story telling.

I’ll do a little bit of explicit reinforcement, though, with my latest tooth-brushing breakthrough. I read, somewhere on the internet, that the way I used fluoridated toothpaste was wrong. I used to brush my teeth, rinse my mouth out with water, spit, and then floss my teeth. What I read pointed out that rinsing your mouth removes the fluoride now coating your teeth, fluoride that you want to *stay* coating your teeth, and that flossing after brushing removes the fluoride you want to stay between your teeth.

I’ve changed my practice, but have I *learned* something? I think Wenger would say not, because it’s a *community* that learns. I’ll learn when I next go to the dentist’s office and talk about my new practice. Someone with more authority, likely my dentist, might reinforce my practice. He might in fact say something like, “Huh. I’ve never really thought about it, but – you know – it makes sense.” And then he might tell other patients, improving the whole community’s practices and knowledge. For Wenger, one of the more important ways communities learn is due to the experiences of its more marginal members, the practices they adjust in response, and the more central members of the community blessing those changes.

Or my dentist might tell me that that’s not the way fluoride works, and my changed practice will die out within the community.

Until such a “negotiation of meaning” happens, I’m just some dude who flosses first.

≤ short music ≥

But. Do the dentist, his hygienists, and his *patients* make up a “community of practice”? I’m no expert, but, at most, I’d say: “*Technically*, but only in the sense that the Pope or a 75-year-old widower is a ‘bachelor’.” Those two are hardly the most central or most evocative examples of bachelorhood, and my dental example is – at best – a similarly weak example of a community of practice. I’m inclined to say it’s too different to fit within the concept’s boundary, for reasons I’ll explain after this next example, one of a *real* community of practice.

Story time again. At around 4 a.m. on January 10th, 2023, I was lying awake because my stupid brain wouldn’t stop thinking about this podcast episode. To shut it up, I read a science fiction story, “Año Nuevo”, by Ray Nayler. It’s a pretty good story; there’s a link in the show notes if you don’t want it partially spoiled. It begins like this:

“So, what do you think?”

“I think they are the crappiest aliens ever.”

That’s a good teaser. It hooks you into the story.

Before I get to the quote that’s the point of this story, I should say that the so-called aliens “look like a bunch of vague, glass sausages, motionless on the beach.” They are colony organisms, something like slime molds, that live from “chemicals in the sand and [the] seawater that filtered down through it. Most of their mass was underneath the sand, blended in with it. They had huge rootlike structures down there, grown down into the beach.”

The beach the aliens are on, doing nothing, is in the real Año Nuevo state park in California, and one of the story’s characters, Illyriana, leads tours to see the aliens twice a week, and sells souvenirs in the Visitors’ Center on three other days. It’s an unsatisfying, dead end job, with tourists who don’t feel the wonder about the aliens that Illyriana thinks they should.

One more story fact. Note, I’m cutting phrases and sentences in the following quote, in the interests of time, so if it sounds a bit jerky, it’s my fault and not Mr. Naylor’s.

“Beach Ball was the littlest of the aliens. The rangers had found him far south, down at the edge of the state preserve, all by himself. He’d been scuffed and gray-looking when they found him, and nearly opaque, which they guessed meant he was ill, or injured. […]

“Because he had seemed so fragile, Beach Ball had been placed in a tank in a back area of the Visitors’ Center. […] Thirty years later, Beach Ball continued to live there in his big plexiglass tank, with plenty of sand to root down into and a complicated sea-water filtration system. Beach Ball seemed fine now – nearly transparent, with a vibrant violet spiral visible inside him. But he had not grown at all.

[…]

“Mostly, […], Beach Ball was the rangers’ unofficial mascot and pet. Although he did nothing at all, […] the employees at the Visitors’ Center attributed everything to Beach Ball. The sign over the coffee maker said, ‘Beach Ball asks that you clean up after yourself.’ A sign by the cash register read: ‘Beach Ball wants to know if you’ve run the credit card receipts.’

“The rangers’ running joke was WWBBD? ‘What Would Beach Ball Do?’ The answer, of course, was always ‘nothing.’ Beach Ball would do nothing at all. Because Beach Ball was totally Zen.”

During the story – and this is the partial spoiler – Beach Ball disappears, causing Illyriana to fear for her job. Now, finally, here’s the quote I want to use:

“Standing there with the techs swabbing and sampling, looking at that empty tank, Illyriana had felt as if her whole life was coming apart. This job – it wasn’t much. It didn’t pay much. But it had been enough: A routine. A kind of family, even: all her coworkers with their little traditions, their inside jokes, and the constant good-natured complaining about the visitors. And it seemed as if Beach Ball had been at the center of it all, in some way, binding all of them together.”

Illyriana is describing a better example of a community of practice, one rather similar to the claims processors Wenger also describes. Here I can finally list off some properties of a community of practice. I’m going to skip the ones I don’t understand.

First, *a joint enterprise*. That is, there’s a shared understanding of what it is that they all do, what they’re trying to accomplish. In the case of workplace communities, the easy part of the joint enterprise is what the bosses want them to do: process claims quickly enough and with few errors, or shepherd visitors throughout the park. But both examples say there’s more to it than that. Claims processing is boring work, done by people who are looked down upon by their bosses. So part of their joint enterprise is to cope with boredom and make the job livable. “They carefully fold into their practice their sense of marginality with respect to the institution, cultivating a subdued cynicism and a tightly managed distance from the job and from the company”. Similarly, everyone around the Visitors’ Center is coping with the fact that the people they’re supposed to serve aren’t worthy of the effort. Thus, a similar cynicism, captured by WWBBD: given the situation, *nothing* they do particularly matters.

Notice that Beach Ball serves as one of Wenger’s reifications. He exemplifies all the pointlessness of the job, and the practices the employees use to cope are organized around him.

A community of practice is something of a way of life.

One reason that I and Dr. Anderson’s dental hygienists aren’t in a community of practice is that we don’t really share an enterprise. We perhaps share a *goal* – keeping paying customers’ teeth free of cavities. (In my case, “the paying customer” is myself.) But, leaving aside that formal goal, what we do with our day has nothing in common. I am completely unaware of what hygienists do to deal with obnoxious customers, being such a pleasure to deal with myself.

≤ short music ≥

The next property of a community of practice is *mutual engagement*. That doesn’t mean constantly working together. Claims processors mostly work alone. Joint work on a claim only happens when one person is having a problem and enlists help. But there are other forms of engagement. They have scheduled group meetings. They eat lunch together. They gossip together on breaks. When “the suits” pass down some edict, they talk together about what it means for how they work. Roberta helps make the day more bearable by providing “an endless supply of snacks”.

Mutual engagement doesn’t mean uniformity. A surgical team is mutually engaged even though each person has a different role. Programmers on a team may be “T-shaped”, with each person having basic competence at most everything, but deeper competence at one particular subset of group practices.

I tend to think of “mutual engagement” with the question: “who would be affected, and how, if someone just… disappeared?” In one medium-term consulting gig, a particular person did just that. No one on his team seemed to particularly care. It took me, as a consultant, embarrassingly long to ask, “Is X no longer working here?” He was, in the sense of collecting his salary, but not in the sense of actually… showing up… or *doing* anything, even from home.

Again, I think my dental hygienist and I fail to connect via mutual engagement. Our interactions are far too limited and infrequent, and if I never had another appointment, no one would notice. I’d guess mutual engagements have to be more on the order of daily or weekly. Even monthly seems like a stretch.

≤ short music ≥

The final property of communities of practice is *identity*. For Wenger, identity is a complicated and subtle topic. It’s the topic of Part 2 of the book, pages 143 to 222, but I have no firm grasp of what’s meant. However:

To Wenger, practicing within a community of practice generates identity. The West African tailor’s apprentices in the previous episode move through a “trajectory” that takes them from novice to expert. In the end result, a part of their identity is as a “tailor”. The claims processors of Wenger’s example are claims processors even when they’re not on the clock. For example, it affects how they interact with doctors when it’s their own health at stake (though in complicated ways).

Note that Wenger understands that people are simultaneously members of multiple communities, so a claims processor is not *just* a claims processor. To him (I think), a lot of identity comes down to how you negotiate (that word again) and reconcile membership in various different communities.

I think Wenger sees identity as being akin to knowledge: a set of experiences that are condensed into patterns. It’s an ongoing story or narrative, where the different scenes have the point: see? That’s who you are. (Note that other people will also be telling stories *about* you to you, and those stories contribute to the pattern.)

Wenger’s claim processor example shows identity as being derived *from* a community of practice. But I think I’m not doing too much violence to his ideas to suggest they also contribute to an existing identity.

Here’s an example. My wife clearly identifies as a veterinarian, and as a college teacher. Those are pretty vague and large-scale to be the sort of communities of practice that lean on “joint enterprise” and “mutual engagement.” But she’s been involved in several successful communities of practice at the Illinois vet school. One was the Agricultural Animal Care and Use Program or AACUP. Another was the Clinical Skills Lab. Her descriptions of how they worked sound like paradise to me, and I bet they’d both tick off all the boxes on an “is this a community of practice?” checklist.

But I don’t think people in those communities *identified* as members, not the way claims processors did or Illyriana did. Instead, those communities were joint enterprises that reinforced *existing* identities. AACUP was about ensuring that veterinary research was consistently humane, and it reinforced the idea that veterinarians are people who got into that business because they love animals and care about them. As with any career, that early passion – that early identity – can be worn down, and AACUP helped reinforce it for people like Dawn.

The Clinical Skills Lab was about giving students more experience, at, well, clinical skills. Things like suturing, haltering, injections, physical exams - except using “animal models” to save wear and tear on the real animals. I have confirmed with Dawn that it reinforced the idea that a professor of veterinary clinical medicine is hands-on, is expected to be a very competent *practitioner*, not only a teacher.

≤ music ≥

Oh dear. Where have we ended up, after all this time? This podcast is all about “huh! this idea from an unrelated field gives me ideas about what I can try in my software work.”

This isn’t… that.

However, I do hope that this episode about better explanations has increased your desire to consciously use examples, counterexamples, and stories when explaining ideas. I really do think they’re useful.

And…

If you are one of the few, the strong, the brave who’ve actually listened all the way to this point, I very much thank you. The next episode will be a return to the normal podcast.