BONUS: Seeing like a personality survey

Download MP3Welcome to oddly influenced, a podcast about how people have applied ideas from *outside* software *to* software. Bonus episode: Seeing like a personality survey.

The purpose of this episode is to help you understand what it means when you see a headline like “Scientists find that people on the political right are less open to experience than people on the left.”

I’m going to be covering the “Big Five” personality traits used by psychology researchers, because that’s the model behind such headlines. I won’t discuss Myers-Briggs. As far as I can tell, it is substantially weaker than the Big Five along all the dimensions I mention here, except for two.

Note: I do refer back to the previous episode. If you haven’t listened to it, the quick summary is that personality traits do a poor job of predicting how individuals will behave in different situations. Knowing that a boy acts extraverted at the dinner table tells you very little about whether he prefers to play alone or with others. It does, however, let you predict how he’ll probably act at dinner tomorrow. There is individual consistency *in* situations but not *between* situations.

≤ music ≥

To start, let’s look at how the Big Five traits were created.

To oversimplify a series of experiments and interpretations down into one story, it went like this: suppose you asked a bunch of people to describe how well particular adjectives applied to them. Adjectives like curious, inventive, outgoing, compassionate, confident, careless, and so on. Probably you’d have had them use a five-point or ten-point scale. So you could say that the value of the “curious” variable for a particular person was 4.

But those adjectives aren’t independent. Someone who gave themselves high marks for curiosity would likely also give themselves high marks for inventiveness, and also, likely, a relatively low mark for consistency. Factor analysis (a statistical technique) boils down the variability in all the adjectives into five underlying variables that account for the majority of the variation. They are most often given these names:

* openness to experience,

* conscientiousness,

* extraversion,

* agreeableness, and

* neuroticism

By the way, here’s one of the ways Myers-Briggs is better: its eight labels don’t contain any that are outright insulting, the way “high in neuroticism” is. As another example, the opposite of being high in Big 5 agreeableness is… being low in agreeableness. That sounds bad. In Myers-Briggs, if your preference is far away from the Thinking end of the scale, you’re not said to be some clod who bumbles around thoughtlessly. You get labeled as Feeling. You can think of yourself as sensitive, perceptive, in touch with the world.

The other advantage Myers-Briggs has is in marketing. Being able to saunter up to someone at a party and say, “I’m an INTP” is way better than saying “I tested 30 on extraversion, 64 on conscientiousness, 83 on openness to experience, and… wait, where are you going? Come back!”

≤ short music ≥

A review paper I link in the show notes details some of the difficulty arriving at those names. “Dimension II has generally been interpreted as Agreeableness […]. Agreeableness, however, seems tepid for a dimension that appears to involve the more humane aspects of humanity--characteristics such as altruism, nurturance, caring, and emotional support at the one end of the dimension, and hostility, indifference to others, self-centeredness, spitefulness, and jealousy at the other. Some years ago, Guilford & Zimmerman […] proposed Friendliness as a primary trait dimension. Fiske […] offered Conformity (to social norms). Reflecting both the agreeableness and docility inherent in the dimension Digman & Takemoto-Chock […] argued for Friendly Compliance […]”

Honestly, it might have been better just to leave it as “Dimension II”. But, because the names do exist, it’s important to remember that Big Five “Agreeableness” is likely *not* what your “folk psychology” means by that word. We want to think it corresponds to some *thing* inside of our minds, but all we *know* is that it labels a cluster in a multidimensional space of answers to survey questions.

Rather than dive into Agreeableness, let’s go back to “openness to experience”. In the previous episode, I noted that I test as strongly open to experience despite how strongly I cherish my routine. Remember that openness to experience is a summary statistic, over many people, of various traits that tend to be correlated. I happen to score high on all but one of the measures that make up the average, so I am – on average – open to experience.

The same thing applies to the popular description of an introvert as being someone who needs to be alone to “recharge their batteries”. The Big Five disagrees. For example, John and Srivastava 1999 gives these facets of high extraversion:

* Sociable

* Energized by social interaction

* Excitement-seeking

* Enjoys being the center of attention

* Outgoing

To the Big Five, if you are sociable, excitement-seeking, and outgoing *but* are not energized by social interaction, you don’t get to say of yourself, “I’m really an introvert, you know, on the inside, despite how I behave in public”. To the Big 5, you’re just a little less extraverted.

You can certainly pick whatever definition you like for the word “introverted”, but be aware that you really ought to caution other people that you mean “needs to be alone to recharge your batteries”. And maybe you should just say that, rather than use a single word with a disputed meaning.

To a psychologist, the value of the Big Five is that the results are stable. For example, if you retake a test some months later, you’ll get a very similar score. Also, you can use the results of one test to predict a person’s result on a different test. In fact, it seems three mutually-ignorant groups in three different countries produced five-factor models from analysis of different personality questionaires, and the result from each model was well correlated with the results from the other two.

(Note: it’s easy to over-interpret this stability. As far as I know, new Big 5 personality tests are validated by seeing how well they correlate with previous tests, which makes it unremarkable that your score on one will be similar to your score on another.)

Now, this stability seems not to fit with the situationist studies in the previous episode. The perhaps flippant response, which I derive from the whimsically pseudonymous “Literal Banana” is that taking a personality survey, any personality survey, is a particular kind of situation. You *behave* in that situation just as consistently as boys at the dinner table do. That is, whatever the underlying *things* it is that the Big Five measures, it’s things that have to do with taking surveys, not necessarily with, say, your behavior in crowds.

At least some trait psychologists disagree. The review article I mentioned uses this analogy: if you knew a student’s grade in math class, would you expect to be able to predict how well she would do on a *single*, specific math problem? No: the grade is a summary of an array of skills, a summary that’s useful for predicting *average* performance over a wide variety of problems. (For example: How well will she do on the math portion of a college placement exam?)

By analogy, the test score for extraversion isn’t meant to be used for predicting behavior at the dinner table, or in the playground, but rather a person’s *average* behavior over *all* situations where extraversion might be relevant.

Given that, in life, we don’t live in average situations but in a sequence of *particular* situations, it’s unsound to use personality scores to think about individuals. No matter how much you as a manager want to survey your team, determine it would be better balanced if you added someone higher in extraversion and agreeableness, and then order HR to find you such an employable unit… well, you can’t always get what you want.

Indeed, the use of personality survey results to understand individuals seems to me an excellent example of /Seeing Like a State/, as described in episodes 17 through 19. People are complicated. So much of what makes them complicated is invisible from the outside. That makes extracting value from people hard and annoying. So, we say, let us find a simplification, an abstraction, a metric, a label that is more pleasant to work with.

See the /Seeing Like a State/ episodes for the pitfalls of that approach.

Another use of personality traits is in sentences where people explain themselves. “Because I’m an introvert, I need some alone time to recharge.” I guess that’s OK if the person you’re talking to requires some genuflection toward science and objectivity before they’ll believe you actually need what you say you need. My hunch, though, is that someday you’ll have to deal with that person being kind of a jerk.

Or not. Maybe you’ll believe that you’re an introvert and that introverts shy away from conflict.

That is: don’t forget that one of the people you’re explaining yourself to is *yourself*. And too often for my taste, that leads to people restricting their choices because they’re seeing *themselves* like a State. As in, “I wouldn’t like pair programming because I’m an introvert.” Much better would be to say, “I haven’t liked pairing the last three times I’ve tried it, so maybe it’s just not for me. But I suppose we can talk about why you think next time will be different.”

≤ music ≥

So now I can tackle “Conservatives test low on openness to experience.” What that *really* says is:

“If you give a bunch of people a Big Five personality survey *and* a survey that condenses their political opinions into a numerical score, you’ll find that, *on average*, there will be a correlation between the two. Those people who test toward the more conservative side of the political scale will tend to test toward the low side of the openness to experience scale, p < 0.05.”

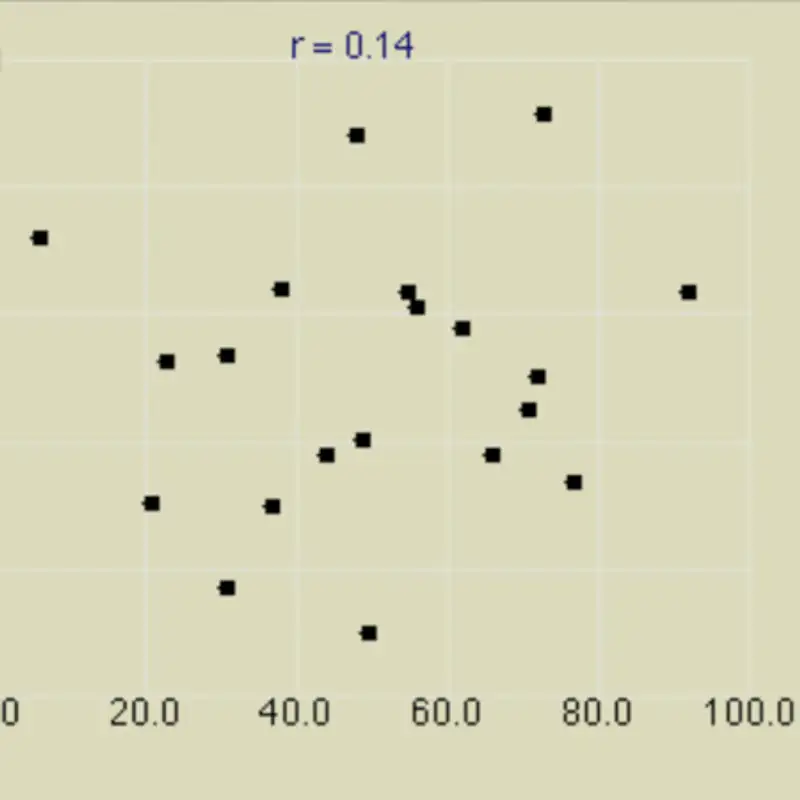

You’ll probably have to go to the original paper to find how *strong* the correlation is. For example, Swedish Master’s student Konstantin Löwe (sorry about the pronunciation) did two large surveys of Swedes. He found, as others had before him, that openness and conservatism were negatively correlated. However, the correlation in both studies was a negative 0.11. As I explained in the last episode, correlations that low look like random noise to the eye.

If you know a person’s score on openness to experience, you know *nothing* about how they’d answered the studies’ survey question, which was:

“Sometimes it is argued that political attitudes can be placed on a left-right scale. Where would you place yourself on such a scale?”

And you’re not even close to knowing whether they’ll *act* conservative in any given situation.

I’m not criticizing Mr. Löwe. He seems to have done a nice study – certainly better than what I did for my Master’s – that happened to be exposed to search engines. I’m criticizing the people, be they researchers, university public relations people, or newspaper writers, who turn data that is significant in the statistical sense into statements that people think are significant – or meaningful – in a *practical* sense.

≤ short music ≥

That’s what I have to say. I do recommend the Literal Banana essays linked in the show notes for a harsher and more flippant take than mine. Thank you for listening.